Beyond the Barracks: How Civilian Involvement in Military Coups Shapes Post-Coup Political Order

My solo book project, Beyond the Barracks, rethinks how we understand the politics of military coups. For decades, scholarship has treated coups as contests waged inside the barracks, where the loyalties of soldiers and officers determine whether regimes stand or fall. Civilians, in this view, appear as passive bystanders or at best supporting actors. Yet this perspective obscures a striking empirical reality: nearly 80 percent of successful coups since 1950 have involved civilians taking active steps to instigate or consolidate the seizure of power. Far from marginal, their participation has consistently shaped not only whether coups succeed, but also the political orders that follow.

The book advances the concept of civilian praetorianism to capture this neglected phenomenon. It argues that the types of civilians who align with soldiers, and the resources they bring, fundamentally shape coup trajectories. Civilian insiders—actors embedded within elite networks and state institutions—possess formal authority, elite resources, and ties to senior officers that allow them to drive coup instigation. Their involvement typically produces preservationist settlements that protect entrenched hierarchies and generate institutionalized, more durable authoritarian regimes. Civilian outsiders—actors on the political periphery, including opposition leaders, ideological movements, and organized constituencies—possess mass-based resources, mobilizing grassroots support and ideological networks to consolidate coups. Yet these coalitions are heterogeneous, fragile, and difficult to manage, making outsider-backed regimes more personalist, redistributive, and prone to instability.

To develop and test this framework, Beyond the Barracks combines comparative historical analysis with original cross-national data. A close study of Sudan’s three major coups (1958, 1969, and 1989) traces how shifts in insider and outsider involvement produced divergent post-coup trajectories in terms of executive authority, power distribution, and regime durability. This is paired with the first global dataset of civilian participation in coups since 1945, providing systematic evidence that these dynamics extend well beyond individual cases. Together, these methods reveal the centrality of civilian actors to the making and unmaking of coup-born regimes.

The book makes three contributions. Conceptually, it shifts the lens of coup research away from a narrow focus on militaries to a broader coalitionary framework. Empirically, it provides the first systematic mapping of civilian roles in coups, complementing detailed casework with comparative reach. Substantively, it reframes debates about what follows coups. Rather than asking only whether they open space for democratization, Beyond the Barracks shows how civilians condition whether post-coup regimes become personalist or institutionalized, redistributive or preservationist, short-lived or enduring.

For scholars, the book integrates coups into wider debates on authoritarian durability, regime formation, and state power. For policymakers and observers, it carries a simple lesson: watching the military is not enough. The durability and character of post-coup regimes depend critically on the civilians who stand behind them.

Read an excerpt of the book’s argument here, published at Armed Forces & Society.

Nasser’s Shadow: Revolutionary Coup Contagion & Mitigation in the Middle East. with Jonathan Powell.

Nasser’s Shadow, co-authored with Jonathan Powell, rethinks how we understand coup contagion—the ways in which coups in one state generate political ripples that can inspire similar acts in neighboring contexts. While popular narratives often depict coups as rapidly contagious, the historical record is far more complex as empirical evidence on whether contagion exists is largely inconsistent. Nasser’s Shadow addresses this persistent puzzle: when and how do coups inspire imitation, and under what conditions do they fail to spread?

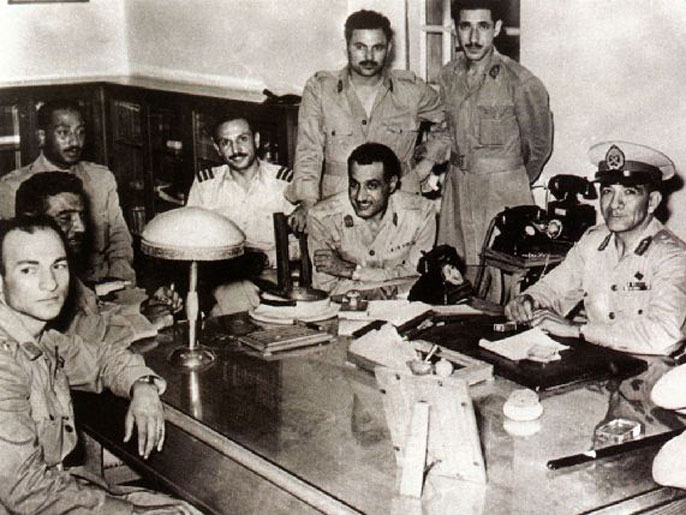

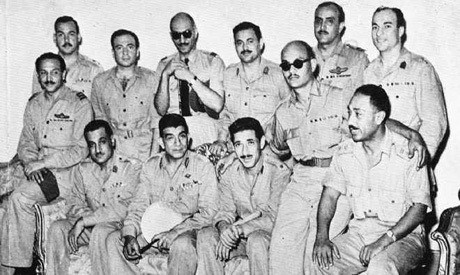

The book centers on the 1952 Egyptian Free Officers coup and Nasser’s rise, tracing the origins, execution, and immediate aftermath of the seizure of power. The initial coup, though dramatic, sent only weak signals to potential imitators; emulation was limited. Over the subsequent years, consolidation, increased visibility, and Nasser’s growing symbolic authority reshaped the perception of the coup abroad. By examining this trajectory, the book demonstrates that contagion is not automatic: signals must reach a certain threshold of credibility, attractiveness, or visibility to influence would-be plotters. Even when signals are positively received, regimes often act strategically to stomp out threats, limiting the ability and disposition of potential imitators before they can act. This interplay between evolving signals and active defensive measures explains why prior quantitative studies have struggled to identify consistent patterns of coup diffusion.

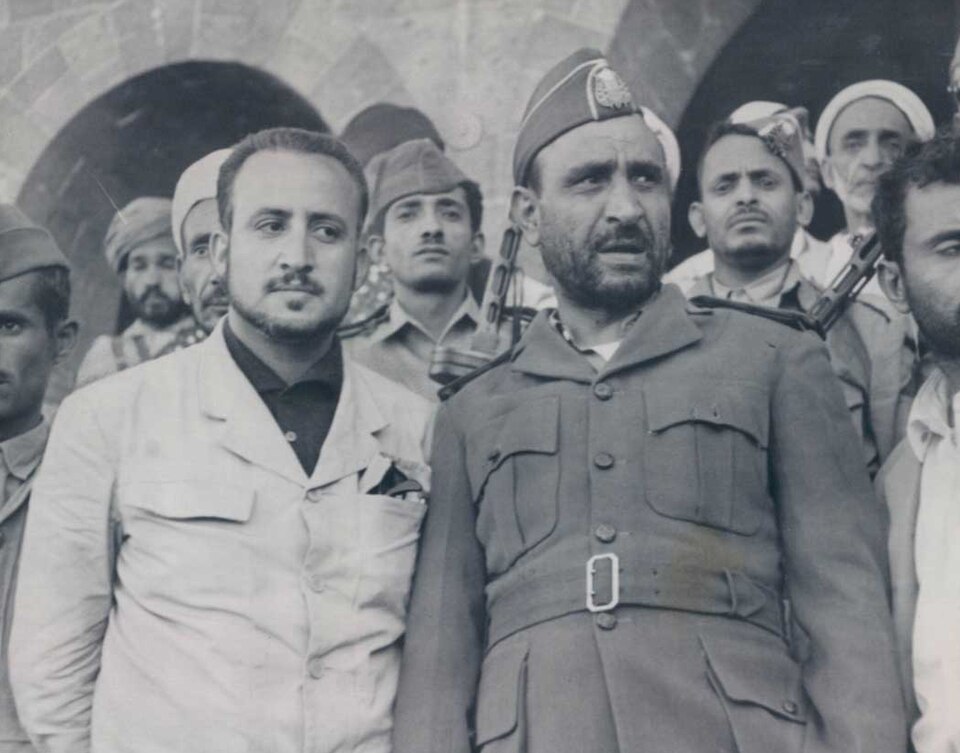

We combine rich historical sources—including archival documents, memoirs, participant testimonies, regional press, and declassified materials—with a comparative lens to reveal both realized coups and aborted conspiracies. This dual focus allows the book to capture the subtle dynamics of political contagion: how coups transmit influence, how actors interpret these signals, and how defensive measures can contain them. In doing so, it provides the first systematic historical account of coup contagion in the Middle East, linking domestic trajectories with regional effects in a way that illuminates both success and failure of imitation.

The book makes three major contributions. Conceptually, it reframes coups as processes with temporal and regional dimensions, emphasizing how signals evolve and are actively contested. Empirically, it offers a rigorous historical account that reconciles anecdotal evidence with inconsistent quantitative results. Substantively, it provides actionable insights for understanding contemporary political instability: recognizing both the signals generated by coups and the preemptive measures they provoke is essential to anticipating ripple effects across borders.

For scholars, Nasser’s Shadow advances debates on political diffusion, authoritarian resilience, and civil–military relations. For policymakers and international observers, it provides a framework to anticipate whether coups are likely to inspire imitation or trigger defensive repression. For journalists and general readers, it offers a vivid historical narrative, portraying Nasser and the Free Officers not merely as national icons, but as regional catalysts whose actions illuminate the mechanics of political contagion—past, present, and ongoing.

Read an excerpt of the book’s argument here, published at International Studies Review.